Chích vắc-xin

Hầu hết các loại vắc xin có sẵn để sử dụng ở Úc đều được tiêm bắp hoặc tiêm dưới da, với một số loại được tiêm trong da hoặc uống. Sử dụng vắc xin theo đúng lộ trình khuyến cáo và sử dụng đúng kỹ thuật là vô cùng quan trọng để đảm bảo đáp ứng miễn dịch tối ưu, giảm thiểu tác dụng phụ và giảm nguy cơ tổn thương cho bệnh nhân.

Routes of administration

Intramuscular

Intramuscular vaccines are administered into the muscle layer of tissue at a 90° angle. Muscle contains a vast amount of blood vessels resulting in increased blood supply which enables the vaccine to disperse easily. In addition, muscles contain dendritic (antigen-presenting) immune cells that initiate a long-lasting immune response. Intramuscular vaccines tend to have fewer side-effects other than redness and pain at the injection site, which are usually mild and short lived.

tiêm dưới da

Subcutaneous vaccines are administered into the subcutaneous, or fatty layer beneath the skin at a 45° angle. Vaccines designed for subcutaneous administration are absorbed at a slower and more constant rate as there is less blood supply in subcutaneous tissue than muscle.

trong da

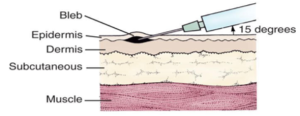

Intradermal vaccines are administered into the outer layers of skin, between the epidermis and the dermis at a 5-15° angle. The epidermal and dermal layers contain many different cells including the antigen-presenting cells (APC’s) that are thought to play a significant role in mediating an efficient and protective immune response to specific vaccines. The 3 main APC’s are macrophages, dendritic cells and B cells. APC’s present specific antigens to particular cells in the immune system that are responsible in eliciting an immune mediated response that in turn creates memory cells and antibodies.

Intradermal vaccination is a unique method of vaccine delivery which requires specific training to ensure vaccine safety and efficacy.

Oral

Oral vaccines activate immune cells in the mucousal membranes lining the gastrointestinal tract which is beneficial in protecting against diseases that affect the gut.

Depending on the vaccine, oral vaccines can come in either tablet or liquid formulation. Liquid vaccines recommended for oral administration should never be injected. Oral vaccines available in tablet form should not be chewed or broken.

Please note, if an infant receiving an oral vaccine spits out a small amount of the dose of vaccine it is still considered a valid dose and doesn’t need repeating. If they spit out most of the dose of vaccine within minutes of receiving it, a repeat dose should be administered at the same visit.

Injectable vaccines

Intramuscular and subcutaneous injection

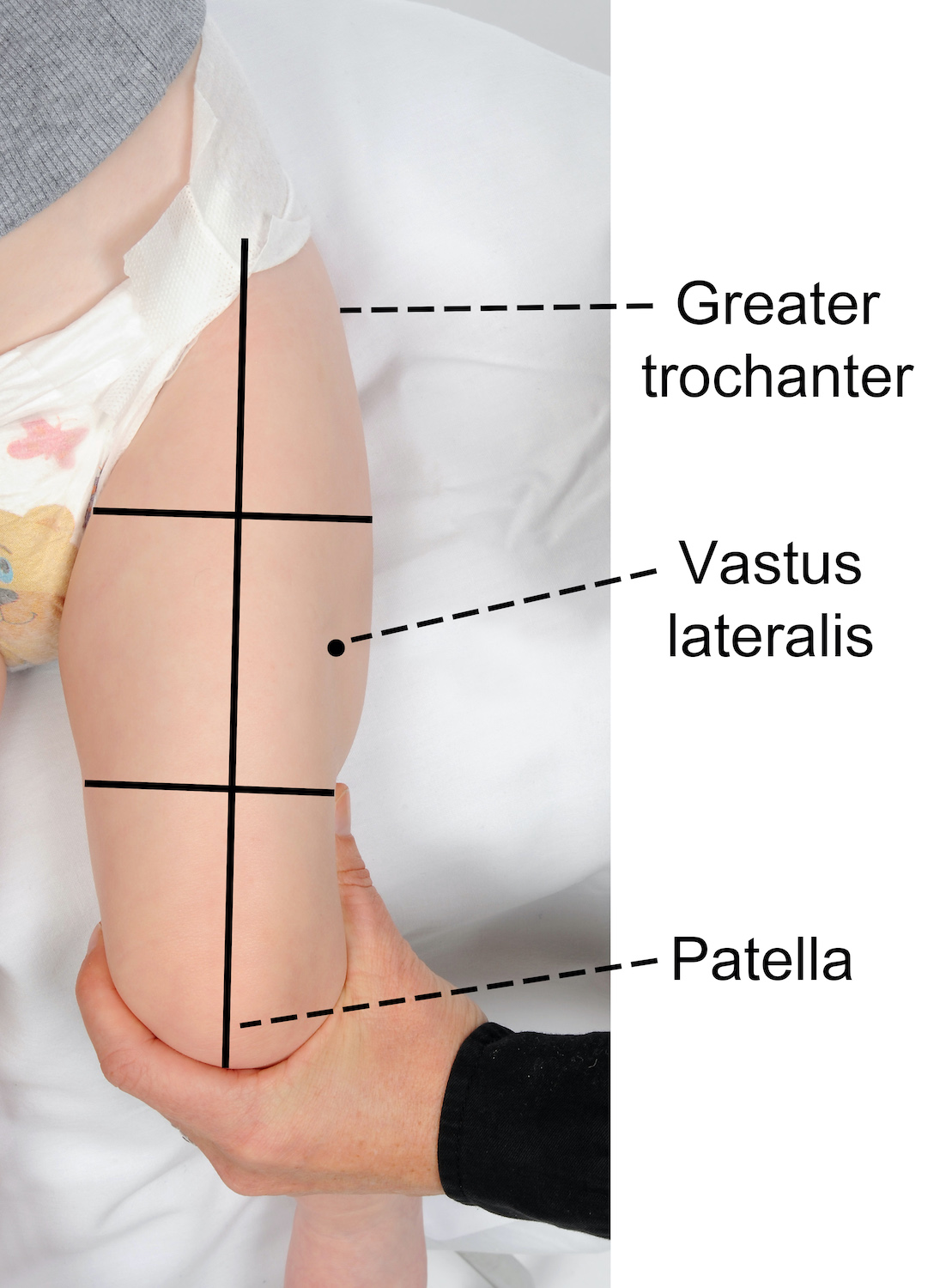

Recommended site for injection in infants < 12 months of age

The recommended injection site is the middle third of the vastus lateralis (anterolateral thigh).

To locate the correct anatomical site for injection:

- ensure the infant’s leg is completely exposed

- locate the upper and lower anatomical landmarks- greater trochanter of femur and patella

- draw an imaginary line between the 2 landmarks down the front of the thigh

- then imagine the thigh is divided into thirds

- the correct injection site is located in the middle third and on the outer aspect of the imaginary line (see images below).

Where only two vaccines are scheduled it is recommended to give one vaccine into each thigh. If more than two vaccines are recommended at the one visit, two vaccines may be given into each thigh ensuring they are separated by 2.5 cm (refer to images below). When administering more than one vaccine into the same thigh, it is important to consider the reactogenicity of each vaccine. Those that are considered more reactogenic should be in different thighs where possible. For example, meningococcal B (Bexsero®) is frequently associated with increased local site reactions.

In some circumstances where the thigh cannot be used (e.g. congenital limb malformations, active eczema or hip brace placement) the deltoid may be used (refer to the recommended site for injection in children ≥ 12 months for guidance).

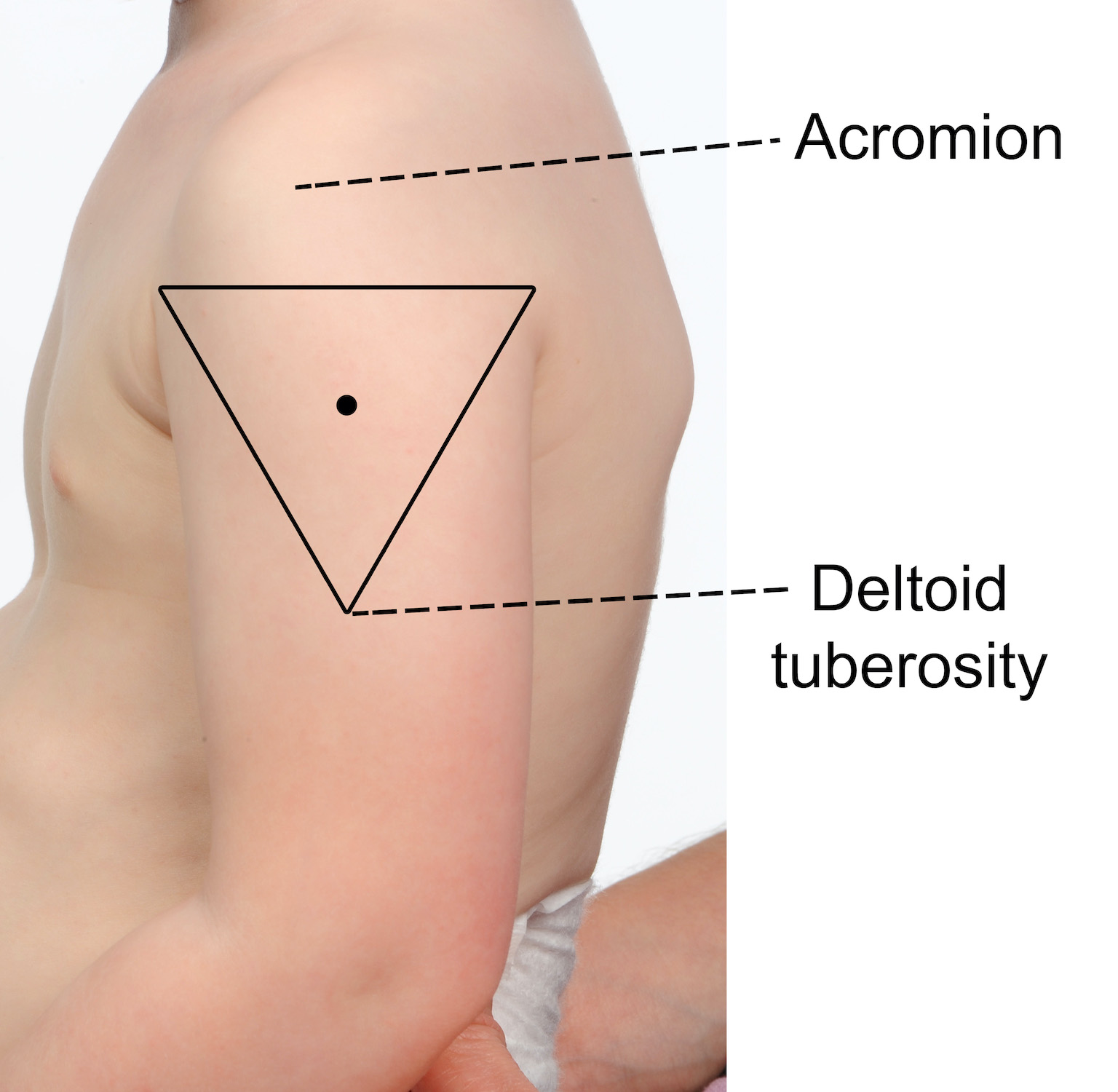

Recommended site for injection in children ≥ 12 months of age, adolescents and adults

The recommended injection site is the deltoid (upper arm).

To locate the correct anatomical site for injection:

- expose the arm completely from the top of the shoulder to the elbow; remove shirt or clothing if needed

- locate the upper and lower anatomical landmarks- acromion (shoulder tip) and the muscle insertion of the deltoid (deltoid tuberosity)

- draw an imaginary inverted triangle below the shoulder tip, using the identified landmarks (see images below)

- the site for injection is halfway between the acromion and the deltoid tuberosity, in the middle of the deltoid muscle (triangle).

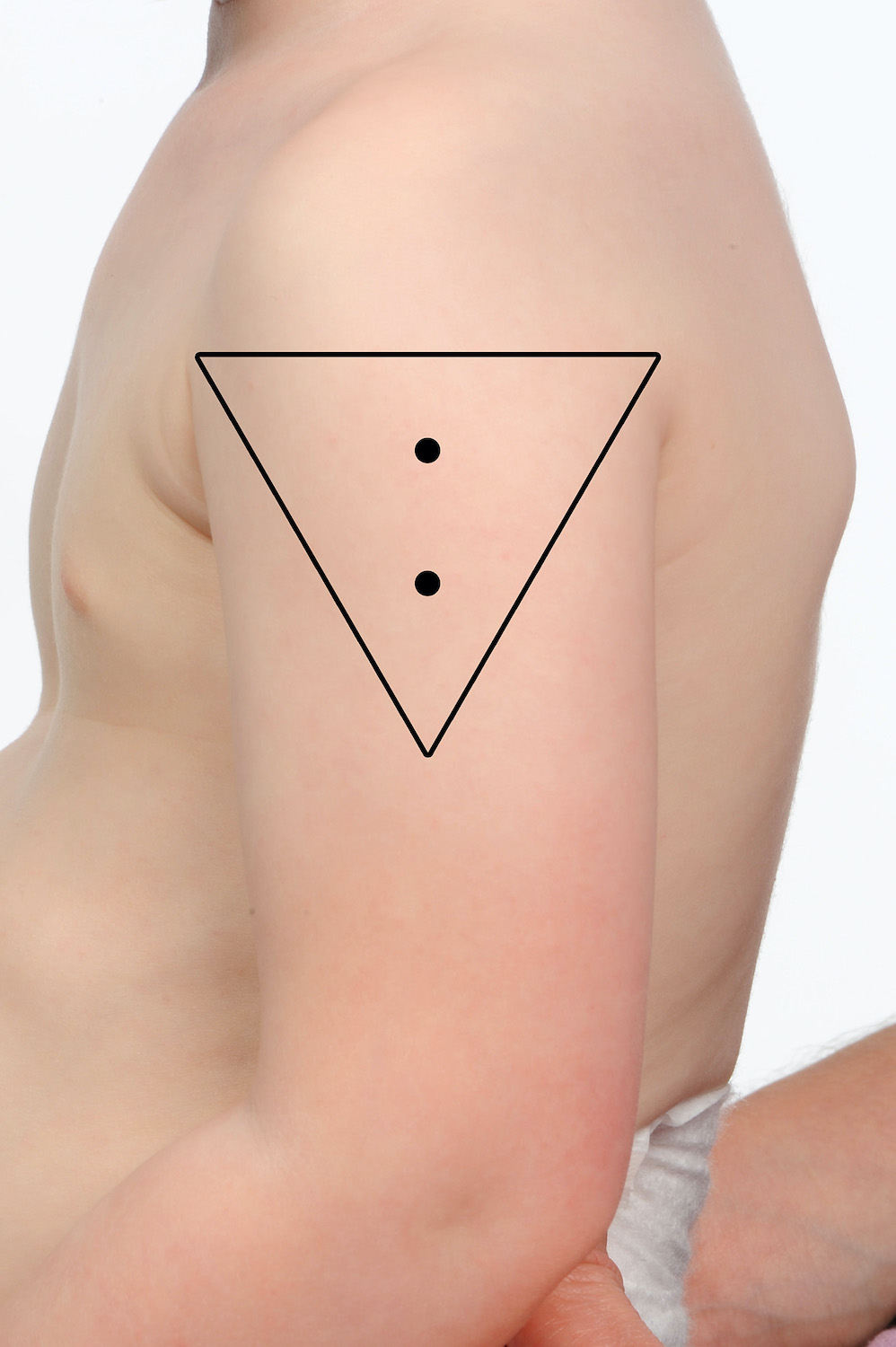

Two or more vaccines may be given into the same deltoid ensuring they are separated by 2.5 cm (refer to images below). When administering more than one vaccine into the same deltoid, it is important to consider the reactogenicity of each vaccine. Those that are considered more reactogenic should be in different deltoids where possible. For example, meningococcal B (Bexsero®) and pneumococcal polysaccharide (Pneumovax® 23) are frequently associated with increased local site reactions.

Utilising the anterolateral thigh may also be required in this age group (e.g. congenital limb malformations, history of auxillary clearance, active eczema or insufficient spacing available). In these circumstances, there is a preference for administering the least reactogenic vaccines via this site (refer to the recommended site for injection in children ≤ 12 months for guidance).

Intradermal injection

Recommended sites for intradermal injection in any age

The recommended sites for intradermal administration are the volar (inner) surface of the mid-forearm or over the deltoid region over where the deltoid muscle inserts into the humerus.

The deltoid region on the left arm is specifically recommended for BCG administration in any age groups as administration at this site minimises the risk of keloid scarring.

Which vaccines can be given intradermally?

Examples of vaccines given by the ID route include BCG Và hepatitis B (for non-responders). Mantoux and Sốt Q tests are also performed intradermally.

Hepatitis B vaccine is usually given by the IM route however there is a small percentage of the population who do not mount a protective immune response to the IM course of hepatitis B vaccines. If they have been deemed by their provider as a non-responder the intradermal route is considered as an alternative [refer to MVEC: Viêm gan B for more information].

WordPress Tables Pluginvắc xin Liều lượng Recommended site BCG (lao) < 12 months 0.05ml

≥ 12 months 0.1mlLeft upper arm over the region where the deltoid muscle inserts into the humerus§ Engerix®-B Adult (hepatitis B)¥ 0.25ml (20mcg/1.0ml) per dose Left upper arm over the deltoid region Jynneos® (MPX) 0,1ml Left upper arm over the deltoid region or the volar surface of the mid-forearm Tuberculin skin test (TST/Mantoux) 0,1ml Volar surface of mid-forearm Q-Vax skin test (Q fever test) 0.1ml of diluted Q-Vax skin test Volar surface of mid-forearm §This is the recommended site to minimise the risk of keloid formation

¥tham khảo MVEC: Viêm gan B for more information on the management of non-respondersIntradermal vaccination technique

- Use a short (10mm) 26-27 gauge needle with a short bevel and a 1ml insulin syringe

- Wear protective eye wear when administering BCG vaccine as eye splashes can ulcerate

- Identify the correct injection site (see Table 1 above)

- Stretch the skin between a finger and your thumb

- Insert the bevel into the dermis with the bevel facing upwards, to a distance of approx. 2mm. The bevel should be visible through the epidermis

You should feel resistance as you inject, if you don’t, the needle may be in subcutaneous tissue. If the injection is not intradermal, withdraw the needle and repeat at a new site. When given correctly, an intradermal injection should raise a blanched bleb.

Preparing the site for injection

The skin at the injection site should be visibly clean prior to administering a vaccine. The swabbing of clean skin before giving an injection is not necessary. If the skin is visibly dirty, clean the site with alcohol wash/single use alcohol swab and allow the site to dry completely before administering the injection. If active/infected eczema is present at the recommended site, consider an alternate site to minimise the risk of injection site abscess. If there is no alternate site suitable, consider cleaning the site with an alcohol based wash/single use alcohol swab and allowing the site to dry completely before injecting.

Recommended needle size, length and angle for administering vaccines

| Age or size of the patient | Needle type | Angle of needle insertion |

| Infant, child or adult for IM injection | 22 – 25 gauge, 25mm in length | |

| Preterm infant or very small infant for IM injection | 23 – 25 gauge, 16mm in length | |

| Very large/obese patient for IM injection | 22 – 25 gauge, 38mm in length | |

| Subcutaneous injection in all patients | 25 – 27 gauge, 16mm in length | |

| Intradermal injection in all patients | 26 – 27 gauge, 10mm in length |  |

* Table adapted from the Sổ tay Chủng ngừa Úc

Positioning for vaccination

Infants and younger children

It is important that children remain still during a vaccination to ensure that the vaccine can be administered into the correct anatomical site, as well as reduce the risk of any unintended injury (eg. needle stick injury). It is important to involve both the child and parent/guardian in discussions when deciding if a child can sit independently or requires support. When positioning a child for vaccination it is important to ensure that they are comfortable and the mobile joints of the limb receiving the vaccine are stable. The immunisation provider must be able to adequately visualise the anatomical landmarks and correct site for injection (deltoid or anterolateral thigh).

Infants can be held in the cuddle position or on their parents lap facing the provider, with the parent/guardian holding their arms securely and their thighs completely exposed. Younger children can be held in the cuddle or straddle positions with their upper arm completely exposed as demonstrated in the clip below.

For infants receiving oral vaccines, it is recommended they are positioned in such a way that the vaccine can be administered via gentle squeezing of the vaccine tube into their inner cheek, such as a feeding position.

Older children, adolescents and adults

It is recommended that older children, adolescents and adults sit in a straight-backed chair with their feet on the floor for vaccine administration. Providers should encourage the vaccine recipient to relax their forearms and rest their hands on their upper thighs, keeping their arms flexed at the elbow to assist in relaxing the deltoid muscle.

Vaccine recipients who are prone to vasovagal responses (fainting) should be vaccinated lying down to prevent unintended injury due to a fall.

Tài liệu

- MVEC: Phản ứng tại chỗ tiêm

- MVEC: Các nốt sần tại chỗ tiêm

- MVEC: Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA)

- DHHS: “Where should I inject vaccines?” poster

Các tác giả: Mel Addison (SAEFVIC Research Nurse, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute) and Rachael McGuire (SAEFVIC Research Nurse, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute)

Đượcxem xét bởi: Francesca Machingaifa (Điều phối viên Y tá Giáo dục MVEC) và Rachael McGuire (Điều phối viên Y tá Giáo dục MVEC)

Ngày: Tháng Bảy 6, 2023

Tài liệu trong phần này được cập nhật khi có thông tin mới và có vắc-xin. Nhân viên của Trung Tâm Giáo Dục Vắc-xin Melbourne (MVEC) thường xuyên xem xét độ chính xác của các tài liệu.

Quý vị không nên coi thông tin trong trang web này là tư vấn y tế chuyên nghiệp, cụ thể cho sức khỏe cá nhân của quý vị hay của gia đình quý vị. Đối với các lo ngại về y tế, bao gồm các quyết định về chủng ngừa, thuốc men và các phương pháp điều trị khác, quý vị luôn phải tham khảo ý kiến của chuyên viên chăm sóc sức khỏe.

Bệnh tăng cường liên quan đến vắc-xin (VAED)

Lý lịch

Vaccine-associated enhanced disease (VAED) is a rare phenomenon where a person who has been vaccinated experiences Một (usually) more severe clinical presentation of an infection than would normally be seen in an unvaccinated person. The mechanismS for how VAED occurs are complex and not clearly understood. Mechanisms may include các behavTôiour của Mộtntibodies generated from vaccination Và abnormal T-cell responses. With the exception of dengue vaccination, where use is restricted to minimiSe VAED risk (see below), vaccines that have been associated with VAED are no longer in use.

Diagnosis

It can be difficult to distinguish between breakthrough disease (when disease occurs in a vaccinated individual because of inadequate vaccine protection) and VAED. To identify a case of VAED, it is necessary to have a clear understanding of the clinical presentation and usual course of the natural disease. VAED is identified by comparison to the natural disease; the clinical presentation of VAED is atypical, modified or more severe. Factors to be considered when assessing a possible case of VAED include:

- expected background rates of disease

- age

- sex

- time of symptom onset after vaccination

- duration of disease

- clinical course and progression of disease

- any co-morbidities.

Various laboratory and clinical diagnostic parameters can be used to help assess the possibility of VAED, including detailed review of all cases of possible vaccine failure.

Associations

Vaccines that have been associated with the development of VAED include an inactivated respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine, an inactivated measles vaccine and a vaccine for dengue fever. (Note that the RSV and measles vaccines associated with VAED are not in use in Australia.)

VAED was observed in the 1960s during clinical trials for an inactivated whole-virus vaccine against RSV. In these trials, some children who had received the vaccine and then were later diagnosed with RSV infection developed more serious disease. As a result, this vaccine was never approved for general use.

People who received an inactivated measles vaccines in the 1960s were found to be more likely to develop an atypical form of measles disease if they were infected. This vaccine is no longer available, and the current measles-containing vaccines are not associated with the same adverse effects.

Dengvaxia, a live-attenuated recombinant dengue vaccine that is currently the only licensed dengue vaccine globally, has also been associated with VAED. If given to someone who has never had dengue infection, Dengvaxia can increase the risk of serious disease if the person is infected with dengue after vaccination. For this reason, Dengvaxia is only recommended in specific groups of people who have already had dengue infection, for prevention of subsequent, more serious secondary infection, within closely defined criteria.

Given the rare possibility of VAED, careful surveillance for potential VAED is an important part of both development of new vaccines, and post-licensure vaccine safety surveillance.

Hàm ý cho liều lượng trong tương lai

All vaccines currently available through the Chương trình Tiêm chủng Quốc gia (NIP) are not linked to VAED.

COVID-19 vaccines are not linked to VAED.

Dengvaxia is registered by the Therapeutics Goods Administration (TGA), but is not currently marketed in Australia.

Tài liệu

- Brighton Collaboration Case Definition of the term “Vaccine Associated Enhanced Disease”

- Gartlan C, Tipton T, Salguero FJ, Sattentau Q, Gorringe A, Carroll MW. Vaccine-associated enhanced disease and pathogenic human coronaviruses. Front Immunol. 2022;13. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.882972

- CHOP: Antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) and vaccines

- Munoz FM, Cramer JP, Dekker CL, et al. Vaccine-associated enhanced disease: Case definition and guidelines for data collection, analysis and presentation of immunization safety data. vắc xin. 2021;29(22):3053–3066. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.01.055

- ATAGI: Clinical advice of the use of Dengvaxia for Australians

- bigay J, Le Grand R, Martinon F, Maisonnasse P. Vaccine-associated enhanced disease in humans and animal models: Lessons and challenges for vaccine development. Front Microbiol. 2022;13. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.932408

Các tác giả: Nigel Crawford (Director SAEFVIC, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute), Adele Harris (SAEFVIC Research Nurse, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute), Georgina Lewis (SAEFVIC Clinical Manager, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute), Julia Smith (RCH Immunisation Fellow) and Francesca Machingaifa (MVEC Education Nurse Coordinator)

Đượcxem xét bởi: Adele Harris (SAEFVIC Research Nurse, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute), Ingrid Laemmle-Ruff (Immunisation Consultant SAEFVIC, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute) Và RachMộtel McGuire (MVEC Điều phối viên y tá giáo dục, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute)

Ngày: April 2024

Tài liệu trong phần này sẽ được cập nhật khi có thông tin mới. Nhân viên của Trung tâm Giáo dục Vắc-xin Melbourne (MVEC, Melbourne Vaccine Education Centre) thường xuyên xem xét độ chính xác của tài liệu.

Quý vị không nên coi thông tin trong trang web này là tư vấn y tế chuyên nghiệp, cụ thể cho sức khỏe cá nhân của quý vị hay của gia đình quý vị. Đối với các lo ngại về y tế, bao gồm các quyết định về chủng ngừa, thuốc men và các phương pháp điều trị khác, quý vị luôn phải tham khảo ý kiến của chuyên viên chăm sóc sức khỏe.

nền tảng vắc xin

Lý lịch

Vắc xin hoạt động bằng cách kích hoạt hệ thống miễn dịch của một cá nhân để hình thành các kháng thể và tế bào ghi nhớ nhằm đáp ứng với mầm bệnh (sinh vật gây bệnh) mà cá nhân đó không cần phải bị nhiễm mầm bệnh đó. Điều này có nghĩa là nếu hoặc khi mầm bệnh đó gặp phải trong tương lai, hệ thống miễn dịch sẽ có thể phản ứng hiệu quả để chống lại nhiễm trùng, giảm thiểu các triệu chứng gặp phải hoặc ngăn ngừa bệnh tật hoàn toàn.

Vắc xin có thể được phân loại thành các loại dựa trên công nghệ mà chúng sử dụng để bắt đầu phản ứng miễn dịch. Công nghệ này được gọi là "nền tảng vắc-xin".

vắc xin bất hoạt

Vắc-xin bất hoạt được tạo ra bằng cách sử dụng các mầm bệnh hoặc các bộ phận của mầm bệnh đã bị giết hoặc vô hiệu hóa mà không thể tái tạo và gây ra các triệu chứng của bệnh. Cách tiếp cận sản xuất vắc-xin này đã được sử dụng trong nhiều thập kỷ để sản xuất vắc-xin chẳng hạn như vắc-xin cho viêm gan A và B, bệnh bại liệt và polysacarit phế cầu khuẩn (Pneumovax 23) vắc-xin. Nuvaxovid (Novavax) là một ví dụ về chế phẩm dựa trên protein đã bất hoạt COVID-19 vắc-xin chỉ sử dụng một phần của vi-rút (protein tăng đột biến).

Một lợi ích của những loại vắc-xin này là chúng an toàn để sử dụng cho hầu hết mọi người kể cả có thai hoặc cho con bú phụ nữ hoặc những người có suy giảm miễn dịch. Tuy nhiên, phản ứng miễn dịch chỉ do cơ chế này tạo ra có thể không mạnh hoặc lâu dài so với phản ứng từ vắc xin sử dụng các nền tảng khác. Để vượt qua thử thách này, có thể cần dùng liều tăng cường hoặc chất bổ trợ (thành phần được thêm vào vắc-xin trong quá trình sản xuất để thúc đẩy phản ứng miễn dịch mạnh hơn và khả năng bảo vệ bệnh tốt hơn).

Vắc xin sống giảm độc lực

Vắc-xin sống giảm độc lực chứa toàn bộ mầm bệnh đã bị làm suy yếu (giảm độc lực) trong phòng thí nghiệm khiến nó ít có khả năng nhân lên và gây bệnh. Ví dụ về vắc-xin sống giảm độc lực bao gồm bệnh sởiquai bị, rubella, varicella (thủy đậu) Và virus rota vắc-xin.

Vắc xin sống giảm độc lực thường tạo ra phản ứng miễn dịch mạnh mẽ và cung cấp khả năng miễn dịch lâu dài, nghĩa là cần ít liều hơn. Nhược điểm chính của việc sử dụng nền tảng này là những loại vắc-xin này không được khuyến nghị sử dụng cho những người bị suy giảm miễn dịch do nguy cơ gây bệnh liên quan đến vắc-xin theo lý thuyết hoặc cho phụ nữ mang thai do khả năng gây hại cho thai nhi. Ngoài ra, chúng mất nhiều thời gian hơn và khó sản xuất hàng loạt hơn vì mầm bệnh cần được nuôi cấy theo các quy trình an toàn sinh học nâng cao trong các phòng thí nghiệm chuyên biệt.

vắc xin di truyền

Vắc-xin di truyền sử dụng một hoặc nhiều gen của mầm bệnh (DNA hoặc mRNA) để kích hoạt phản ứng miễn dịch. Vắc xin COVID-19 Corminaty (Pfizer) và Spievax (Moderna) là những ví dụ về vắc xin mRNA và chúng chứa mã di truyền dành riêng cho phần protein gai của vi rút.

Vắc xin di truyền có thể được sản xuất nhanh hơn các phương pháp sản xuất truyền thống vì quá trình phát triển có thể bắt đầu ngay khi có trình tự di truyền của mầm bệnh. Vắc-xin di truyền chỉ có khả năng tạo ra protein và không thể sửa đổi vật liệu di truyền của vật chủ (người nhận vắc-xin) (DNA hoặc mRNA).

Vắc xin vector virus

Vắc-xin vec-tơ virus không sao chép và sao chép là loại vắc-xin di truyền. Chúng hoạt động bằng cách sử dụng một loại vi-rút đã được sửa đổi (vectơ vi-rút), không gây bệnh ở người, để mang một phần mã di truyền của mầm bệnh vào tế bào người.

Trong vắc-xin véc tơ vi-rút không sao chép, các tế bào của từng cá nhân sau đó sẽ tạo ra các protein (kháng nguyên) đặc hiệu cho mầm bệnh để kích hoạt phản ứng miễn dịch. Vắc-xin COVID-19 Vaxzevria (AstraZeneca) là một ví dụ về vắc-xin véc tơ vi-rút không sao chép.

Việc sao chép vắc-xin véc-tơ vi-rút có cơ chế tương tự nhưng cũng sẽ tạo ra các hạt vi-rút mới để xâm nhập vào các tế bào tiếp theo của con người, cho phép đáp ứng miễn dịch nhanh hơn và mạnh hơn. Tái tạo vắc-xin véc tơ vi-rút mô phỏng tốt nhất quá trình lây nhiễm tự nhiên và do đó tạo ra phản ứng miễn dịch mạnh mẽ và có thể được sử dụng với liều lượng thấp hơn.

Mặc dù các vec tơ vi rút được dung nạp tốt và có khả năng sinh miễn dịch cao ở hầu hết mọi người, nhưng khả năng miễn dịch đã có từ trước đối với vec tơ vi rút được sử dụng có thể cản trở đáp ứng miễn dịch đối với vắc xin.

Vắc-xin dựa trên hạt nano

Vắc xin dựa trên hạt nano đã nhận được sự quan tâm ngày càng tăng trong những năm gần đây do hồ sơ an toàn tốt và khả năng sinh miễn dịch cao.

Vắc xin hạt nano được chế tạo bằng cách gắn các thành phần chính đã chọn của mầm bệnh (chẳng hạn như protein tăng đột biến COVID-19 hoặc DNA của vi rút) vào một hạt nano đã được thiết kế (chất mang nano). Hạt nano này thường là một hạt giống vi-rút được thiết kế (một phân tử bắt chước vi-rút nhưng không lây nhiễm). Những hạt nano này có tính ổn định cao và ít bị phân hủy hơn so với vắc-xin protein truyền thống. Gardasil 9 (vi rút gây u nhú ở người) và vắc-xin Nuvaxovid (Novavax COVID-19) là những ví dụ về phương pháp này.

Tài liệu

- Cẩm nang Tiêm chủng Úc: Các loại vắc-xin

- Bệnh viện Nhi đồng Philadelphia, Trung tâm Giáo dục Vắc xin: Chế tạo vắc xin: Vắc xin được sản xuất như thế nào

- Những giới hạn trong miễn dịch học: Tiến bộ và những cạm bẫy trong quá trình tìm kiếm vắc xin SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) hiệu quả

Các tác giả: Daniela Say (Thành viên tiêm chủng MVEC) và Nigel Crawford (Giám đốc SAEFVIC, Viện nghiên cứu trẻ em Murdoch)

Đượcxem xét bởi: Rachael McGuire (Điều phối viên Y tá Giáo dục MVEC) và Francesca Machingaifa (Điều phối viên Y tá Giáo dục MVEC)

Ngày: Tháng Tư 1, 2023

Tài liệu trong phần này được cập nhật khi có thông tin mới và có vắc-xin. Nhân viên của Trung Tâm Giáo Dục Vắc-xin Melbourne (MVEC) thường xuyên xem xét độ chính xác của các tài liệu.

Quý vị không nên coi thông tin trong trang web này là tư vấn y tế chuyên nghiệp, cụ thể cho sức khỏe cá nhân của quý vị hay của gia đình quý vị. Đối với các lo ngại về y tế, bao gồm các quyết định về chủng ngừa, thuốc men và các phương pháp điều trị khác, quý vị luôn phải tham khảo ý kiến của chuyên viên chăm sóc sức khỏe.

Các buổi tiêm chủng của hội đồng Victoria

Each local council throughout Victoria offers regular immunisation sessions for the administration of all funded National Immunisation Program (NIP) vaccines. Sessions are free to attend and people of all ages requiring NIP vaccines can be vaccinated. Sessions are run by accredited nurse immunisers with medical support. Some councils may also choose to have additional vaccines such as meningococcal (Nimenrix® or Bexsero®), influenza and chickenpox vaccines available for purchase for those who do not meet the eligibility criteria for funded vaccines [see resources]. All vaccines administered are recorded on the Đăng ký Chủng ngừa Úc (AIR).

Please refer to the tables below for contact details of your local council to obtain further information regarding session times.

Metropolitan councils

| Council | Telephone number | Immunisation sessions |

|---|---|---|

| Banyule City Council | (03) 9490 4222 | Banyule immunisation session times |

| Bayside City Council | (03) 9599 4444 | Bayside immunisation session times |

| Boroondara City Council | (03) 9278 4444 | Boroondara immunisation session times |

| Brimbank City Council | (03) 9248 4000 | Brimbank immunisation session times |

| Cardinia Shire Council | 1300 787 624 | Cardinia immunisation session times |

| City of Casey | (03) 9705 5200 | Casey immunisation session times |

| Darebin City Council | (03) 8470 8562 | Darebin immunisation session times |

| Frankston City Council | 1300 322 322 | Frankston immunisation session times |

| Glen Eira City Council | (03) 9524 3333 | Glen Eira immunisation session times |

| Greater Dandenong City Council | (03) 8571 1000 | Dandenong immunisation session times |

| Hobsons Bay City Council | (03) 9932 1000 | Hobsons Bay immunisation session times |

| Hume City Council | (03) 9205 2200 | Hume immunisation session times |

| Kingston City Council | 1300 653 356 | Kingston immunisation session times |

| Knox City Council | (03) 9298 8000 | Knox immunisation session times |

| Manningham City Council | (03) 9840 9333 | Manningham immunisation session times |

| Maribyrnong City Council | (03) 9688 0145 | Maribyrnong immunisation session times |

| Maroondah City Council | (03) 9298 4598 | Maroondah immunisation session times |

| Melbourne City Council | (03) 9340 1451 | Melbourne immunisation session times |

| Melton City Council | (03) 9747 7200 | Melton immunisation session times |

| Monash City Council | (03) 9518 3555 | Monash immunisation session times |

| Moonee Valley City Council | (03) 9243 8888 | Moonee Valley immunisation session times |

| Moreland City Council | (03) 9240 1111 | Moreland immunisation session times |

| Mornington Peninsula Shire | (03) 5950 1000 | Mornington immunisation session times |

| Nillumbik Shire Council | (03) 9433 3111 | Nillumbik immunisation session times |

| Port Phillip City Council | (03) 9209 6383 | Port Phillip immunisation session times |

| Stonnington City Council | (03) 8290 1333 | Stonnington immunisation session times |

| Whitehorse City Council | (03) 9262 6197 | Whitehorse immunisation session times |

| Whittlesea City Council | (03) 9217 2170 | Whittlesea immunisation session times |

| Wyndham City Council | (03) 9742 0777 | Wyndham immunisation session times |

| Yarra City Council | (03) 9205 5555 | Yarra City immunisation session times |

| Yarra Ranges Shire Council | 1300 368 333 | Yarra Ranges immunisation session times |

Regional councils

| Council | Telephone number | Immunisation sessions |

|---|---|---|

| Alpine Shire Council | (03) 5755 0555 | Alpine immunisation session times |

| Ararat Rural City Council | (03) 5355 0200 | Ararat immunisation session times |

| Ballarat City Council | (03) 5320 5850 | Ballarat immunisation session times |

| Bass Coast Shire Council | (03) 5671 2211 | Bass Coast immunisation session times |

| Baw Baw Shire Council | (03) 5624 2411 | Baw Baw immunisation session times |

| Benalla Rural City Council | (03) 5760 2600 | Benalla immunisation session times |

| Buloke Shire Council | 1300 520 520 | Buloke immunisation session times |

| Campaspe Shire Council | (03) 5481 2200 | Campaspe immunisation session times |

| Central Goldfields Shire Council | (03) 5461 0610 | Central Goldfields immunisation session times |

| Colac Otway Shire Council | (03) 5232 9400 | Colac-Otway immunisation session times |

| Corangamite Shire Council | (03) 5232 7100 | Corangamite immunisation session times |

| East Gippsland Shire Council | (03) 5153 9500 | East Gippsland immunisation session times |

| Gannawarra Shire Council | (03) 5450 9333 | Gannawarra immunisation session times |

| Glenelg Shire Council | (03) 5522 2211 | Glenelg immunisation session times |

| Golden Plains Shire Council | (03) 5220 7111 | Golden Plains immunisation session times |

| Greater Bendigo City Council | (03) 5434 6000 | Bendigo immunisation session times |

| City of Greater Geelong | (03) 4215 6962 | Geelong immunisation session times |

| Greater Shepparton City Council | (03) 5832 9700 | Shepparton immunisation session times |

| Hepburn Shire Council | (03) 53482306 | Hepburn immunisation session times |

| Hindmarsh Shire Council | (03) 5391 4444 | Hindmarsh immunisation session times |

| Horsham Rural City Council | (03) 5382 9777 | Horsham immunisation session times |

| Indigo Shire Council | 1300 365 003 | Indigo immunisation session times |

| Latrobe City Council | 1300 367 700 | Latrobe immunisation session times |

| Loddon Shire Council | (03) 5494 1200 | Loddon immunisation session times |

| Macedon Ranges Shire Council | (03) 5422 0333 | Macedon Ranges immunisation session times |

| Mansfield Shire Council | (03) 5775 8555 | Mansfield immunisation session times |

| Mildura Rural City Council | (03) 5018 8100 | Mildura immunisation session times |

| Mitchell Shire Council | (03) 5734 6200 | Mitchell immunisation session times |

| Moira Shire Council | (03) 5871 9222 | Moira immunisation session times |

| Moorabool Shire Council | (03) 5366 7100 | Moorabool immunisation session times |

| Mount Alexander Shire Council | (03) 5472 1364 | Mount Alexander immunisation session times |

| Moyne Shire Council | 1300 656 564 | Moyne immunisation session times |

| Murrindindi Shire Council | (03) 5772 0333 | Murrindindi immunisation session times |

| Northern Grampians Shire Council | (03) 5358 8700 | Northern Grampians immunisation session times |

| Pyrenees Shire Council | (03) 5349 1100 | Pyrenees immunisation session times |

| South Gippsland Shire Council | (03) 5662 9200 | South Gippsland immunisation session times |

| Southern Grampians Shire Council | (03) 5573 0444 | Southern Grampians immunisation session times |

| Strathbogie Shire Council | (03) 5795 0000 | Strathbogie immunisation session times |

| Surf Coast Shire Council | 1300 610 600 | Surf Coast immunisation session times |

| Swan Hill Rural City Council | (03) 5036 2333 | Swan Hill immunisation session times |

| Towong Shire Council | (02) 6071 5100 | Towong immunisation session times |

| Rural City of Wangaratta | (03) 5722 0888 | Wangaratta immunisation session times |

| Warrnambool City Council | (03) 5559 4855 | Warrnambool immunisation session times |

| Wellington Shire Council | 1300 366 244 | Wellington immunisation session times |

| West Wimmera Shire Council | (03) 5585 9900 | West Wimmera immunisation session times |

| City of Wodonga | (02) 6022 9300 | Wodonga immunisation session times |

| Yarriambiack Shire Council | (03) 5398 0100 | Yarriambiack immunisation session times |

For any feedback relating to this page please contact us here.

Tài liệu

- DHHS: Lịch tiêm chủng của Victoria và tiêu chí đủ điều kiện nhận vắc xin miễn phí

- MVEC: Đăng ký Chủng ngừa Úc

Tác giả: Rachael McGuire (Y tá nghiên cứu SAEFVIC, Viện nghiên cứu trẻ em Murdoch)

Đượcxem xét bởi: Francesca Machingaifa (Điều phối viên y tá giáo dục MVEC)

Ngày: tháng 2 năm 2022

Tài liệu trong phần này được cập nhật khi có thông tin mới và có vắc-xin. Nhân viên của Trung Tâm Giáo Dục Vắc-xin Melbourne (MVEC) thường xuyên xem xét độ chính xác của các tài liệu.

Quý vị không nên coi thông tin trong trang web này là tư vấn y tế chuyên nghiệp, cụ thể cho sức khỏe cá nhân của quý vị hay của gia đình quý vị. Đối với các lo ngại về y tế, bao gồm các quyết định về chủng ngừa, thuốc men và các phương pháp điều trị khác, quý vị luôn phải tham khảo ý kiến của chuyên viên chăm sóc sức khỏe.

niềm tin về vắc-xin

At MVEC we strongly encourage people to seek answers to their questions and to be well informed with evidence-based information. We know that nearly half of all parents have some concerns about immunising their children, ranging from minor concerns to more serious degrees of vaccine hesitancy. Many people also have questions about COVID-19 vaccines for themselves and their families.

There is a lot of information available to people, particularly on the internet, which can be quite overwhelming. There is also a lot of misinformation, and conspiracy theories, and it can be hard to know which information sources to trust and what is true. Research suggests that information alone is not enough to address people’s concerns about immunisation, even when it comes from recommended sources. That is because vaccine conversations matter, and how we discuss vaccines is often just as important as what information is shared.

Talking to people who have questions about vaccines

One of the most effective strategies to address people’s questions and concerns about vaccines is through a discussion with a trusted health care provider like a GP, nurse, paediatrician or midwife. Effective conversations are non-judgemental and help guide people towards accepting vaccination.

Having a combative conversation with a person who has questions about vaccines is never helpful. If possible, try to work out where the person may sit on the vaccine hesitency spectrum. They may have only minor concerns, more serious concerns or they may refuse vaccines all together. This often becomes apparent quite quickly as you start the conversation and helps you tailor your conversation accordingly.

Here are the key steps to have an effective vaccine conversation:

1. Find out all of the person’s questions and concerns

- Start with an open-ended question, like “What concerns do you have?”

- Try to just listen and not jump in and correct their beliefs straight away. This is what we call “resisting the righting reflex”

- Encourage them to share all their concerns before you start responding. They may even mention their most important concern last.

- At this point, once they have had a chance to list their concerns, summarise them to check your understanding.

2. Acknowledge concerns and share knowledge

- Not everyone is “vaccine hesitant”. Having questions is very normal, especially with the newer COVID-19 vaccines. People are likely to be more receptive to what you have to say if you acknowledge their concerns without judgement.

- It is helpful to ask if you can share what you know about vaccine safety and effectiveness and provide some good resources and information. Try to keep your explanations clear and check for understanding.

- At this point, it is good to reinforce their motivation to accept vaccination.

3. Discuss disease severity

- It is always good to bring the discussion back to centre on disease severity, rather than focusing exclusively on the vaccines. This reminds people why we are vaccinating and reinforces the benefit.

4. Recommend vaccination

- Lastly, make a clear and strong recommendation to have the vaccine(s). This reinforces the importance of vaccination and clearly shows that you believe this is the best way to protect the person against vaccine preventable diseases.

- If it is possible and the person is willing, deliver the vaccine(s) or explain where they need to go to receive them.

5. Continue the conversation

- If the person is not yet ready to accept vaccination, keep the communication open and invite them back at a later time to continue the conversation.

Talking with friends and family can also have an influence on people’s vaccine hesitancy. If you’re someone who wants to encourage others to vaccinate, you can take some of the strategies we recommend for healthcare providers into your discussions with people in your life.

This seems obvious, but the best approach is not to judge people, correct them, or jump into battle. This just entrenches people’s beliefs and makes them defensive. And they probably won’t trust you or want to talk to you openly about this topic anymore!

How to tackle misinformation

We’ve all heard people spreading misinformation and myths about vaccines. While it can be tempting to try to correct misinformation whenever you hear it, this can actually give the issue more oxygen. But if you notice that misinformation is spreading widely and beginning to affect people’s vaccination behaviour, it may be time to step in.

If an individual is spreading misinformation, try to speak with them privately. It’s not effective to have a public debate, either in person or online. Acknowledge the emotion and try to look for the truth together.

If you are debunking a particular myth, start by clearly restating the truth. Then, explain why the myth is untrue, and provide an alternative explanation for what the person is experiencing.

For example, if someone believes that the flu vaccine gives them the flu because they feel sick after the vaccine, it’s not enough to simply tell them that is untrue. Explain why this is untrue – the vaccine contains a killed virus that cannot cause the flu. Then follow this with an alternative explanation for the person’s symptoms – this is your body generating an immune response to the vaccine, and these symptoms are much more mild and brief than actual flu symptoms.

Finally, end by restating the truth. People remember what we say first and last, and what we say more than once. Make sure it’s the truth and not the myth that sticks in their minds.

Tài liệu

Talking to people who have concerns

- NCIRS Sharing Knowledge About Immunisation (SKAI) project

- MumBubVax: Talking about immunisation for mothers and babies

- The Conversation: Everyone can be effective advocate for vaccination- here’s how

Communicating about COVID-19 vaccines and vaccine safety

- World Health Organization: COVID-19 vaccines- safety surveillance manual

- Pre print MJA: Communicating with patients and the public about COVID-19 vaccine safety: recommendations from the Collaboration on Social Science in Immunisation

- COSSI: A COVID-19 vaccine strategy to support uptake amongst Australians: Working Paper November 2020

- ABC news: How to talk to friends and family feeling unsure about COVID-19 vaccines

- The COVID-19 Vaccine Communication Handbook

Addressing misinformation or talking about vaccination in online forums

- World Health Organization: How to respond to vocal vaccine deniers in public

- BMC Public Health: How organisations promoting vaccination respond to misinformation on social media: a qualitative investigation

- UNICEF: Vaccine misinformation management guide

- Tips on countering conspiracy theories and misinformation

Các tác giả: Margie Danchin (Senior Research Fellow, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute) and Rachael McGuire (SAEFVIC Research Nurse, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute)

Đượcxem xét bởi: Margie Danchin (Group Leader, Vaccine Uptake Group, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute) and Jess Kaufman (Research Fellow, Vaccine Uptake Group, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute)

Ngày: June 2021

Tài liệu trong phần này được cập nhật khi có thông tin mới và có vắc-xin. Nhân viên của Trung Tâm Giáo Dục Vắc-xin Melbourne (MVEC) thường xuyên xem xét độ chính xác của các tài liệu.

Quý vị không nên coi thông tin trong trang web này là tư vấn y tế chuyên nghiệp, cụ thể cho sức khỏe cá nhân của quý vị hay của gia đình quý vị. Đối với các lo ngại về y tế, bao gồm các quyết định về chủng ngừa, thuốc men và các phương pháp điều trị khác, quý vị luôn phải tham khảo ý kiến của chuyên viên chăm sóc sức khỏe.

thủy đậu

Cúm là gì?

Varicella (chickenpox) is a highly contagious disease caused by infection with the varicella-zoster virus (VZV). After a person recovers, the virus stays dormant (inactive) within the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal nerves and can later be reactivated, presenting as herpes zoster (shingles).

Cần để ý những gì

Symptoms begin 7 to 21 days after exposure to the virus. Fever, rhinorrhoea (runny nose) and lethargy lasting 1 to 2 days are the first signs of disease (prodromal period). This is followed by the appearance of a pruritic (itchy) rash which is initially maculopapular (flat discoloured areas and raised areas) then becomes vesicular (fluid-filled blisters). The vesicles rupture then crust over, usually within 10 to 14 days. The rash can cover any part of the body including inside the mouth, on the scalp, eyelids and genital area. Unvaccinated children may experience 200 to 500 lesions. Approximately 5% of cases will be subclinical (symptoms are so mild they remain undetected under clinical examination).

Most cases of varicella are self-limiting (will resolve by itself), but complications can include secondary bacterial infections, septicaemia (blood infections), pneumonia, meningitis, encephalitis and acute cerebellar ataxia (uncoordinated muscle movements).

Varicella infections during pregnancy can result in congenital varicella syndrome in the child. Symptoms of congenital varicella syndrome include skin scarring, eye anomalies, limb defects and neurological malformations. The risk of congenital varicella syndrome is higher when infection occurs in the second trimester. Infants who have been exposed to varicella through a maternal varicella infection can develop herpes zoster, but this is rare.

Despite vaccination, some people may still develop disease if exposed to infection. This is known as breakthrough disease. Breakthrough varicella symptoms are usually mild. Patients are typically afebrile and develop fewer skin lesions. People experiencing breakthrough disease are contagious and can transmit disease to others.

Bệnh lây truyền qua đường nào

Varicella is transmitted by inhaling respiratory droplets that are made airborne when an infected person coughs or sneezes. It can also be spread by direct contact with the fluid inside the vesicles or through contact with items that have been contaminated with vesicle fluid.

A person with varicella is considered infectious for 1 to 2 days prior to the onset of the rash until all the lesions have crusted.

Dịch tễ học

Varicella is highly infectious. More than 80% of non-immune household contacts of an infected individual will develop disease.

Prior to the introduction of vaccination in Australia in 2005, there were 240,000 cases of varicella annually, resulting in 1,500 hospitalisations and an average of 7 to 8 deaths. The rate of hospitalisation for varicella infection was reduced to 2.1 per 100,000 people in 2013. Most of these children were aged under 18 months, the scheduled age for varicella vaccination. (NB: Children can be safely vaccinated from 9 months of age.)

Infants less than 4 weeks of age, premature neonates, unimmunised adolescents, có thai women and immunosuppressed individuals are at các greatest risk of severe disease and complications if they become infected.

Phòng ngừa

Vaccines can provide protection against varicella infection.

| Nhóm tuổi | Vaccine brand, antigen, dose and route | ||

| Varilrix (varicella) 0.5 mL SC | Varivax (varicella) 0.5 mL SC | Priorix Tetra (measles, mumps, rubella, varicella) 0.5 mL SC | |

| < 9 months | |||

| ≥ 9 months to < 12 months | ✓ | ✓ | |

| ≥ 12 months to < 12 years | ✓ | ✓ | ✓^ |

| ≥ 12 years | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

^ MMRV combination vaccines must not be given as the first dose of measles-containing vaccine in children < 4 years due to the higher rates of fevers (see precautions and contraindications below).

* Whilst not registered for use in those aged ≥ 12 years, ATAGI recommends it may be used up to 14 years. MVEC advises that its use may also be considered in older adults when protection against measles, mumps and rubella is also required.

shaded boxes – varicella vaccine is routinely offered on the NIP as a single dose at 18 months. AIR will consider vaccination from 12 months of age as a valid dose.

ô vuông tô màu không đăng ký để sử dụng ở nhóm tuổi này.

shaded boxes indicate live-attenuated vaccines.

khuyến nghị

A single dose of varicella vaccination (in combination with measles, mumps and rubella) is funded on the NIP at 18 months of age. (NB: Children can be safely vaccinated from 9 months of age.)

A second dose (not funded) is recommended for greater protection to reduce the incidence of breakthrough disease. A minimum interval of 4 weeks is recommended between doses of live-attenuated vaccines.

Anyone non-immune aged 14 years and over should receive a catch-up course of 2 doses (administered 4 weeks apart) for adequate protection.

Household contacts of suy giảm miễn dịch individuals are recommended to complete their immunisation schedule on time.

Common vaccine side effects

Phản ứng tại chỗ tiêm (occurring in the first 48 hours) and fever (occurring 5 to 12 days after vaccination) are common side effects.

A maculopapular or vesicular rash (with 2 to 5 lesions) occurring 5 to 26 days after vaccination will develop in approximately 5% of vaccine recipients. If this occurs, it is recommended that lesions should remain covered until they crust over to avoid potential transmission of the virus to others. Transmission of the vaccine virus to contacts is extremely rare. Worldwide there have only been 11 documented cases of virus transmission from a recently vaccinated person to unvaccinated individuals.

Precautions and contraindications

All varicella vaccines are live-attenuated vaccines and are therefore contraindicated in pregnancy and in those with immunocompromise.

Children and adults who have been diagnosed with IFNAR1 should seek advice from an immunisation specialist or immunologist prior to vaccination.

There are recommended intervals between immunoglobulins or other blood products and administration of injected live-attenuated vaccines. Refer to MVEC: Vắc xin sống giảm độc lực và globulin miễn dịch hoặc sản phẩm máu.

When administered as the first dose of an MMR-containing vaccine, MMRV vắc xinS have been associated with higher rates of fever in children. It is therefore recommended that MMRV vaccines are administered as the second dose only of the 2-dose course of MMR in children under 4 years of age.

Phòng ngừa sau phơi nhiễm

Vaccination (first or second dose) can be provided within 3 to 5 days of exposure to varicella (provided it is not contraindicated). This can reduce the likelihood of varicella disease developing.

Neonates (whose mother develops infection up to 7 days prior to delivery or within 2 days after delivery), infants under 1 month of age (if mother is seronegative), pregnant women, premature infants (while still hospitalised, regardless of maternal serology) or immunosuppressed individuals who are exposed to varicella disease should receive Zoster Immunoglobulin (ZIG).

Repeat doses of ZIG may be given if a person is exposed to varicella again more than 3 weeks after the first dose of ZIG.

Tài liệu

- RCH Kids health information: Varicella fact sheet

- Australian Immunisation Handbook: Varicella

- MVEC: Zoster

- MVEC: Vắc xin sống giảm độc lực và globulin miễn dịch hoặc sản phẩm máu

Tác giả: Rachael McGuire (Research Nurse, SAEFVIC, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute)

Đượcxem xét bởi: Rachael McGuire (MVEC Education Nurse Coordinator) and Katie Butler (MVEC Education Nurse Coordinator)

Ngày: October 2023

Tài liệu trong phần này được cập nhật khi có thông tin mới và có vắc-xin. Nhân viên của Trung Tâm Giáo Dục Vắc-xin Melbourne (MVEC) thường xuyên xem xét độ chính xác của các tài liệu.

You should not consider the information on this site to be specific, professional medical advice for your personal health or for your family’s personal health. For medical concerns, including decisions about vaccinations, medications and other treatments, you should always consult a healthcare professional.